If you’re building a SaaS product, you’ve likely noticed a gap between the number of people using your platform and the number of people paying for it. In everyday terms, you might have lots of users exploring your app, but far fewer customers contributing to your revenue. Understanding the difference between “users” and “customers” in a SaaS context is crucial for sustainable growth. It’s not just semantics—users and customers play different roles in your business, and knowing how to convert users into paying customers can make or break your SaaS venture.

May 08 2025 • 34 min read • 6746 words

Users vs. Customers in SaaS: Understanding the Difference and Driving Conversions

- Users vs. Customers: What’s the Difference?

- The Logic of Converting Users into Customers

- Not All Users Will Become Customers (And That’s Okay)

- Measuring Conversion Profitability: CAC, CLV, and Conversion Rates

- Short-Term vs. Long-Term Value: When Users Turn into Profitable Customers

- Segmenting Users and Optimizing the Conversion Funnel

- Identifying High-Value vs. Cost-Heavy Users: A Framework

Users vs. Customers: What’s the Difference?

In the context of SaaS, users and customers are related but distinct groups:

- A user is anyone who uses your product. This could be a free trial user, someone on a freemium plan, or even an active user within a paid account (for example, an employee using software their company purchased). Users engage with your software’s features and derive value from using it, but they are not necessarily the ones who pay for that value. In other words, users use the product.

- A customer is someone who pays for your product. Customers are the source of revenue – they have converted from simply using the service to actually purchasing a subscription, license, or plan. A customer could be an individual (in a B2C SaaS or small business scenario) or an entity like a company (in B2B SaaS) that pays for a number of user accounts. In short, customers buy the product (or the access to it).

To illustrate this difference, consider a common SaaS example: a project management platform with a free tier. Jane signs up for free and uses the platform with her team; she is a user. Her team finds it valuable and eventually Jane’s manager purchases the premium plan for more features – that manager (or the company) is now a customer. Jane and her teammates remain users (they use the tool daily), and the company is the paying customer. In a B2B scenario, often the person or group that makes the purchase decision (customer) is not identical with every end-user of the product. In a B2C scenario (say a solo freelancer tool), the user and customer might be the same person once they pay.

The table below highlights some key differences between users and customers in a SaaS environment:

| Aspect | User | Customer |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | An individual who uses the SaaS product’s features. May be on a free plan, trial, or using a paid product but without being the purchaser (e.g. an employee end-user). | An individual or organization that pays for the SaaS product. This is the buyer or subscriber who provides revenue in exchange for value. |

| Relationship | No direct revenue exchange is required to be a user. The user’s “transaction” is that they get to experience the product (often in return for providing their time, data, or word-of-mouth). | Engages in a financial transaction with the SaaS provider. The customer has an ongoing business relationship (e.g. a subscription) and expects service, support, and value for the money. |

| Primary Concerns | Usability and utility of the product. A user cares about what the software does for them: is it solving their problem, easy to use, and enjoyable? (They can walk away at any time if not satisfied, especially if they haven’t paid.) | Return on Investment (ROI) and value. A customer cares about getting their money’s worth: does the product provide enough benefit to justify the cost? They focus on outcomes, support, and that the product continues to meet their needs so they don’t churn. |

| Example | A marketer using a free social media scheduling tool to test its features; a team member using a project app under the company’s free trial; a student using a limited free version of design software. | The marketer’s company when it decides to upgrade and pay for the scheduling tool’s premium plan; the team’s company buying the project app subscription after the trial; the individual student once they purchase a paid license for the design software. |

Both users and customers are vital to a SaaS business, but in different ways. Users represent your product’s reach and potential – a large user base can indicate popularity and growth opportunities. Customers represent your revenue and sustainability – without converting some users into paying customers, a SaaS business can’t survive for long. Importantly, the transition from user to customer is the journey we often call conversion, and it’s a core focus of SaaS growth strategies. Next, we’ll delve into why SaaS companies often gather users first and then aim to turn them into customers, and how this fits into common business models.

The Logic of Converting Users into Customers

One of the defining strategies in SaaS business models is the idea of “land users, then expand into customers.” Instead of requiring a purchase up front, many SaaS platforms lower the barrier by letting people start as users (through free accounts, free trials, or freemium plans). The logic is straightforward: by getting users in the door and demonstrating value to them, you increase the likelihood that a portion of them will be willing to pay for additional features or continued use. This approach is especially popular in product-led growth strategies, where the product itself (rather than a sales pitch alone) drives the conversion.

Why start with users? For one, offering a free experience – whether it’s a limited-feature freemium version or a time-limited trial – reduces friction. Potential customers can see the product in action and solve a problem before committing dollars to it. This expands your reach: many more people will sign up for a free or trial version than those willing to pay sight unseen. Each sign-up is a user acquired, and each active user becomes a candidate for conversion to paid. Essentially, it widens the top of your funnel: you might get 1,000 users to try your app, hoping that perhaps 100 of them eventually become paying customers. Without the free entry point, you might have only gotten a fraction of those 1,000 to even consider your product.

This model also leverages a form of network effect and social proof: as more users join and use the free tier, they may invite colleagues or friends, talk about your product, or contribute content (depending on the app). This can create a community and buzz around the product, which in turn attracts more users. Over time, the user base grows, and even if only a percentage convert, the absolute number of customers increases as the funnel feeds itself. Think of popular SaaS like Slack, Dropbox, or Zoom – they gained millions of free users, who then helped introduce these tools into workplaces or workflows. Eventually, teams or companies decided to pay for the premium version (making them customers), often because so many employees (users) were already hooked on the free version.

From a business perspective, converting users to customers is about moving from engagement to monetization. Early on, a startup may focus on user growth (getting people to love the product), but ultimately it must show revenue growth. The free users represent future revenue potential. The conversion funnel exists to realize that potential: marketing brings in users, the product and onboarding activate them, and then upsell prompts or sales efforts turn a subset of those engaged users into paying customers.

It’s important to note that a “customer” in SaaS often implies an ongoing revenue stream (subscriptions, renewals). So conversion isn’t a one-time win; it kicks off a customer lifecycle. Once a user becomes a customer, you continue to nurture that relationship through customer success efforts, ensuring they get value and hopefully renew (or even expand their spend). In essence, the logic of converting users to customers is about building a sustainable revenue engine: use a broad top-of-funnel (users) to feed a growing base of recurring revenue (customers).

However, this approach only makes sense if it’s done strategically. Simply accumulating users without a plan or ability to convert them can become a vanity metric exercise. In the next section, we’ll discuss why not all users will become customers and why that’s okay – as long as you know how to identify and focus on the right users to convert.

Not All Users Will Become Customers (And That’s Okay)

It would be wonderful if every user who tried your SaaS product fell in love and pulled out their wallet. In reality, only a fraction of users will convert into paying customers. In fact, in freemium models it’s common that well under 10% of free users ever upgrade to a paid plan. This is not a sign of failure by itself; it’s a natural outcome of casting a wide net. The key is understanding which users are likely to become customers and focusing your efforts on them, rather than assuming every user has equal likelihood or value.

Why don’t most users convert? There are many reasons: some users were just browsing or needed your tool for a one-off task and leave after that. Some might be price-sensitive and will stick to free solutions no matter what. Others may love the concept but not find enough value in practice, or they encounter friction and give up before reaching the “aha!” moment in your product. In some cases, a user might want to upgrade but lack authority (for example, an employee loves the free version but needs their manager’s approval to buy the paid version – if that approval never comes, the user remains a non-paying fan). Additionally, competitors are always a factor: a user might compare your product with alternatives and choose a different solution or juggle multiple free tools instead of paying for one.

It’s important to accept that a large portion of your user base is essentially passive or low-value from a revenue standpoint. For instance, if you have a free tier, you might find that many users sign up, poke around, and never return. Others use your free service regularly but deliberately avoid paying by staying within free limits. These segments will likely never convert, or their probability of conversion is extremely low. Chasing every user indiscriminately to push them toward purchase could waste resources and even annoy users with aggressive tactics.

So how do you figure out which users are worth targeting for conversion? This is where data and segmentation come in. Successful SaaS companies analyze user behavior and attributes to identify high-potential users. For example, you might discover that users who perform certain actions (like importing their data, using a key feature repeatedly, or inviting team members) within the first week are far more likely to become paying customers. These actions could define a Product-Qualified Lead (PQL) – essentially a user who has experienced the core value of the product and has a strong usage profile indicating a good fit. Similarly, you might segment users by their use case or profile: a freelance hobbyist using your tool for fun is less likely to pay than a small business owner using it to streamline their operations. By evaluating factors like company size, industry, or role (if you collect that data during sign-up), you can prioritize users who match your target customer profile.

It’s also useful to track engagement metrics: Active users vs. inactive users. An active user who logs in frequently and utilizes many features is a better prospect than someone who signed up once and forgot about the app. Not all active users will pay, but those who clearly derive value have a higher chance of seeing the worth in upgrading for more. On the other hand, if someone hasn’t returned since day one, sending them repeated “please upgrade” emails is likely futile – they haven’t even become a true user, let alone a customer candidate. Your resources are better spent re-engaging them to use the product (so they become active users first) rather than pushing a sale.

In sum, conversion is a filtering process. Out of all your users, you aim to filter in the ones who have both need and willingness to pay for additional value. This could be a small percentage of the user base, and that’s normal. The business model works if that small percentage is large enough in absolute terms and if each customer brings in sufficient revenue (more on measuring that soon). The rest of the users might remain free forever – and that can still be beneficial to your business in indirect ways, which we’ll discuss later.

Before that, let’s talk about how to measure the economics of this user-to-customer conversion engine. How do you know if converting, say, 5% of your users is enough? How do you evaluate whether your current conversion rate and spend are sustainable? This is where metrics like CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and CLV (Customer Lifetime Value) come into play.

Measuring Conversion Profitability: CAC, CLV, and Conversion Rates

Turning users into customers isn’t just a product challenge – it’s also an economic one. You want to ensure that the money and effort you invest to acquire and convert users will pay off in the long run. Three key metrics help evaluate this: Conversion Rate, Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC), and Customer Lifetime Value (CLV). Let’s break down each and see how they interact:

Conversion Rate

In our context, conversion rate usually refers to the percentage of users who become paying customers over a given period or funnel stage. You might measure, for example, “free trial conversion rate” (what percentage of trial users end up subscribing) or “freemium conversion rate” (what percentage of users on the free plan eventually upgrade). A higher conversion rate means you’re better at turning users into customers. Conversion rates can vary widely depending on the product and model – some well-optimized SaaS trials might convert 25%+ of trial users to paid, whereas freemium platforms might see under 5% of free users upgrade. By tracking this metric, you gauge how effectively your funnel is working. It also lets you simulate outcomes: if you know that roughly 1 in 20 free users converts, you can estimate how many customers you’ll get from any influx of users.

Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC)

CAC is the average cost to acquire one paying customer. This includes marketing and sales expenses, and sometimes a portion of onboarding costs. For example, if you spend $10,000 on a marketing campaign and it yields 100 new customers, your CAC is $100 per customer. In a product-led model with lots of free users, you have to be a bit careful in defining CAC: you might spend money to acquire users (through ads, content marketing, etc.) who have not yet paid. So one way to think of CAC in that scenario is to include all the costs to get those users in and then divide by the number of customers that emerged from that user pool. For instance, suppose you spent that same $10,000 and got 1,000 free sign-ups, out of which 100 converted to paid. Effectively, you paid $10 per sign-up (user) but $100 per customer. Both numbers are useful: $10 is the cost per acquired user, and $100 is the cost per acquired customer. CAC typically refers to the latter. It’s a critical metric because it tells you how expensive it is to buy revenue. If your CAC is too high relative to what those customers pay you, you have a problem.

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV or LTV)

This is the total revenue you expect to earn from a customer over the entire time they remain a customer. In subscription businesses, CLV is often calculated as Average Revenue Per User (per month) × average customer lifespan (in months), sometimes adjusted for profit margins or discounting, but the basic idea is how much a customer is worth over time. For example, if your average customer pays $50 per month and stays subscribed for 24 months on average, that customer’s CLV is $50 × 24 = $1,200. CLV is crucial because SaaS businesses often lose money on a customer upfront but recover it over time. A high CLV means each conversion is quite valuable in the long run, whereas a low CLV might not justify much spending to acquire customers.

The interplay of these three metrics determines if your user-to-customer conversion strategy is financially sound. A fundamental rule in SaaS is that CLV should exceed CAC, ideally by a healthy margin. Many investors and experts often cite a target LTV:CAC ratio of 3:1 or higher – meaning the lifetime value is at least 3 times the cost to acquire the customer. If it’s 1:1 or worse (CLV equal to or less than CAC), you are essentially spending a dollar to get a dollar (or losing money on every customer), which is not sustainable without some other compensating factor.

Let’s use a simple model to tie these together. Read more below:

Premium content

Log in to continue

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Value: When Users Turn into Profitable Customers

One of the challenging aspects of SaaS is that the payoff from converting a user into a customer often comes over an extended period. Unlike a one-time sale, SaaS subscriptions accrue revenue over months or years. This means that some user acquisition strategies can look like a money-loser in the short term but actually be a big winner in the long term once those users convert and stick around as customers.

Consider a classic example: a SaaS company offers a 30-day free trial for a premium plan. During those 30 days, the user is not paying anything, yet they are using the product (incurring hosting costs, maybe support if they ask for help, etc.), and the company might have spent marketing dollars to get that trial signup in the first place. At the end of the trial, say 20% of users decide the product is worth paying for and subscribe. The other 80% leave without converting. At the moment the trial ends, if you only look at immediate cash flow, the company has spent money on all 100% of those users, but only 20% are bringing money in. Initially, this could be a net cost. However, those 20% now start their paid subscriptions. If the product truly delivers value, many of them might continue paying for months or years. Over time, the revenue from the converted customers can far outweigh the costs of providing the trial to everyone.

For instance, let’s say each of those converted customers pays $50 per month. In the first month after conversion, you have 20 customers × $50 = $1000 in revenue. Meanwhile, assume the cost of running 100 trials (infrastructure, support, etc.) plus the marketing to get them was $2000 – so at trial’s end you’re “down” $2000. But fast-forward 4 months: if most of those 20 customers are still paying, by month 4 you’ve received ~$4000 in revenue (minus ongoing costs). You’ve now not only recovered the initial costs, but you’re in profit from that cohort. Every additional month those customers stay becomes pure incremental profit. In the long run, this trial strategy clearly pays off, provided your conversion rate and retention are healthy.

This kind of dynamic is why SaaS companies and their investors pay close attention to metrics like CAC payback period (how many months of subscription to recover the acquisition cost) and churn rate (what percentage of customers cancel each month or year). A scenario that’s unprofitable in the first 1-2 months can become a cash cow by month 12 if retention is good. Conversely, if customers don’t stick around long, you might never recoup your costs.

See real-life examples below:

Premium content

Log in to continue

It’s easy to think of users acquired through organic or free channels as costing nothing – after all, you didn’t spend ad money to get them to sign up. However, every user has a cost. Even if you aren’t paying for clicks or doing expensive marketing, each user account uses server resources (storage, bandwidth, compute power), possibly triggers customer support or requires onboarding emails, and adds overhead in terms of data management and security. As your user base grows, supporting even non-paying users can become a significant operational expense for a SaaS company. This is why the decision to offer a free plan or trial must be strategic: you’re essentially subsidizing free users in hopes of future returns. But what about those users who never convert to paying customers? Are they purely a drag on the business? Not necessarily. Smart SaaS businesses try to extract indirect value from non-paying users to make the free usage worthwhile. Here are a few ways free users can contribute value:

Word-of-Mouth and Referrals

Even if a user doesn’t pay, if they love your product they might tell others about it. They could bring in colleagues, friends, or their organization – some of whom might become customers. In this sense, a free user can act as a marketing agent for you. Many freemium SaaS products encourage this by building referral loops: for example, offering extra free features or credits if a user invites someone else. The original user still may not pay, but if their referral converts, the company gains a customer thanks to them. Some companies explicitly measure a “virality factor” – how many additional users each user brings. If each free user on average brings in 0.1 more users (directly or indirectly), that can compound growth. Even without formal referrals, a satisfied free user increases brand awareness through casual mentions on social media or in industry communities.

Network Effects and Ecosystem Value

In platforms where user activity itself creates value (like content creation, data contributions, or network size), free users are extremely important. For example, consider a SaaS that connects businesses with clients or a community platform: having many users (even free) makes the platform more attractive and valuable to everyone, including paying customers. A social scheduling tool might count on lots of free users engaging with content, which in turn draws businesses to use the platform to reach that audience. In cases like these, free users effectively are part of the product. Their presence and activity is the “content” or “network” that paying customers want access to. So even if those users don’t pay, they provide value by making the service richer for the customers who do.

Product Feedback and Improvement

Users who never pay can still be a rich source of feedback and data. By observing how free users interact with your product, you can learn what features are popular, what hurdles they face, and where they drop off. They might fill out surveys, participate in beta tests, or suggest new features. This feedback can be used to improve the product for everyone, thereby increasing future conversion or retention of paying customers. It’s often said that free users “vote with their time” – if they stick around and use certain features heavily, that’s a signal of value. Conversely, if large numbers of free users abandon the product at a certain point, that highlights an issue to fix. In short, free users can help you make a better product-market fit, which ultimately leads to more paying customers down the road.

Monetizing via Alternative Means

While classic SaaS usually doesn’t show ads, some products do monetize free users indirectly. For example, a free-tier user base can be used for upselling other paid products or services, or cross-promoting a partner’s offering (carefully, so as not to degrade user experience). In some cases, companies might offer a free software tool and monetize through a marketplace or transaction fees (where paying customers are on the other side of a transaction). The specifics vary, but the idea is that a user doesn’t necessarily have to pay you subscription dollars to be monetized; there could be other creative models if your user base is large and engaged. That said, most B2B SaaS stick to the straightforward model of aiming to convert free users to direct revenue and using the above non-monetary benefits as a secondary justification for free usage.

Given these potential benefits, how should you handle free users who are consuming resources but not converting? The key is balance and boundaries. You want to be generous enough that free users stick around and add value, but not so generous that they can forever get everything they need without paying (if they are actually a target customer). This is where having well-designed free-tier limits or trial limitations is important. For instance, you might allow a certain number of projects, seats, or data usage for free, and beyond that point the user needs to upgrade. Truly casual or small-scale users will stay under the cap (and that’s fine – they promote your product by being part of the user base), whereas serious users will hit the limit and then either churn out (not ideal, but then they likely weren’t a fit or ready to pay) or they’ll convert because they see enough value to justify paying for more.

It’s also wise to monitor cost-heavy free users. Sometimes a small number of free users can consume a disproportionate amount of resources (think of a “power user” who never upgrades, or a free user who stores massive amounts of data if you don’t enforce limits). These users can actually erode your margins. If you identify them, it may be necessary to intervene – for example, by politely informing them of usage caps, suggesting a paid plan for their level of usage, or optimizing your systems to reduce their cost impact. It’s a delicate dance: you value all users, but you also need to run a business. Often, implementing fair usage policies or graceful upgrade prompts can turn a cost-heavy free user into a paying customer or at least keep their usage in check.

Segmenting Users and Optimizing the Conversion Funnel

Converting users to customers effectively often comes down to delivering the right message or experience to the right user at the right time. Not all users are alike, and a one-size-fits-all approach to conversion will miss opportunities. Segmentation is the practice of grouping your users into meaningful categories so you can tailor your engagement and conversion tactics to each group. Alongside segmentation, you want to refine your conversion funnel – the step-by-step journey a user takes from first encountering your product to becoming a loyal customer – to plug any leaks and smooth the path.

How to Segment Users

Start by identifying factors that distinguish users in ways relevant to conversion. Some useful segments for SaaS include:

By engagement level For example, new active users, power users, inactive users, etc. A user who uses your app daily versus one who signed up but never completed the onboarding should not be treated the same. You might segment into cohorts like “Completed onboarding” vs “Never completed onboarding” and have different follow-up approaches for each.

By source or acquisition channel Users who came from an organic referral might behave differently than those who came from a paid ad or a software review site. If you know the source, segment by it. Perhaps you discover that referrals convert at a higher rate – you might invest more there. Or users from certain campaigns might need extra education, indicating you should tweak either the campaign targeting or your onboarding for that group.

By user profile or demographics If applicable, segment by attributes like company size, industry, role, or region. For instance, a user who indicates they are a “CTO at a mid-size company” during sign-up might be a high-value lead for an enterprise plan, whereas a “Student” might never pay but could spread the word. You might funnel the CTO into a higher-touch sales-assisted conversion track (maybe send their info to a sales rep or show them enterprise-focused messaging), whereas the student gets standard automated nurturing and perhaps prompts to refer others instead of upgrade.

By behavior and feature usage This is often the richest way to segment in a product-led growth model. Look at what users actually do in your app. Examples:

- Segment users who have hit a usage limit or attempted to use a premium feature (they’ve discovered a need for the paid version).

- Segment those who achieved a key milestone (like created their first project, or integrated your app with another service) – these “activated” users have experienced value and are prime targets to upsell.

- Conversely, segment users who signed up but haven’t done critical actions (like never created a project or never uploaded data). These people are at risk of dropping off; they may need re-engagement or help to see value (rather than an upgrade pitch at this point).

Concrete tactics in summary: ensure users experience value quickly, communicate the benefits of upgrading in a timely and relevant way, segment and personalize outreach where possible, and reduce friction at the conversion point (make it easy to subscribe or talk to sales). Even small improvements at each stage can compound to significantly higher overall conversion rates.

Identifying High-Value vs. Cost-Heavy Users: A Framework

As your user base grows, you’ll want to continually assess the quality of those users. Two terms often discussed are high-value users and cost-heavy users. Let’s define these:

High-Value Users

These are users who either have already become valuable customers or show strong potential to become valuable in the future. They might generate high revenue (e.g. by being on a top-tier plan or by likely upgrading to one), have long lifetime potential, or contribute significant indirect value (like referrals or strategic brand presence). High-value users are the ones you want more of; they justify extra effort and investment to delight and retain. They pay well, use the product a lot (in a positive way), and are happy. Action: focus on retaining them, upselling if appropriate, and making sure they remain satisfied. They might also be tapped for testimonials or case studies (since they see value).

Cost-Heavy Users

These are users who consume a lot of your resources relative to the revenue they bring (if any). They might be free users with disproportionately high usage (for example, using large amounts of storage or API calls on your free tier), or even paying customers on a low plan who require excessive support or have extremely expensive usage patterns that your pricing hasn’t accounted for well. These users can drag down your margins. In some cases, cost-heavy users are a normal part of doing business (you’ll always have some heavier users balanced by lighter ones), but if you have too many, it can be problematic.

To manage your business effectively, you can create a simple evaluation model for users. Think of it as a two-sided score: one side for the value a user generates or is likely to generate, and one side for the cost they incur. By comparing the two, you can categorize users and decide on actions.

Above all, think holistically about user value. Every user who signs up has some kind of value and some kind of cost. Your job is to maximize the total value you get (in revenue, learning, and advocacy) and minimize the total cost, across your entire user base. Sometimes that means nurturing a free user community because it seeds your pool of future customers and champions. Other times it means tightening up and focusing on the profitable customer segments to improve your margins. In most cases, it means a blend of both: cultivating a large, engaged user base and systematically converting a healthy portion of them to paying customers.

Premium content

Log in to continue

You might like

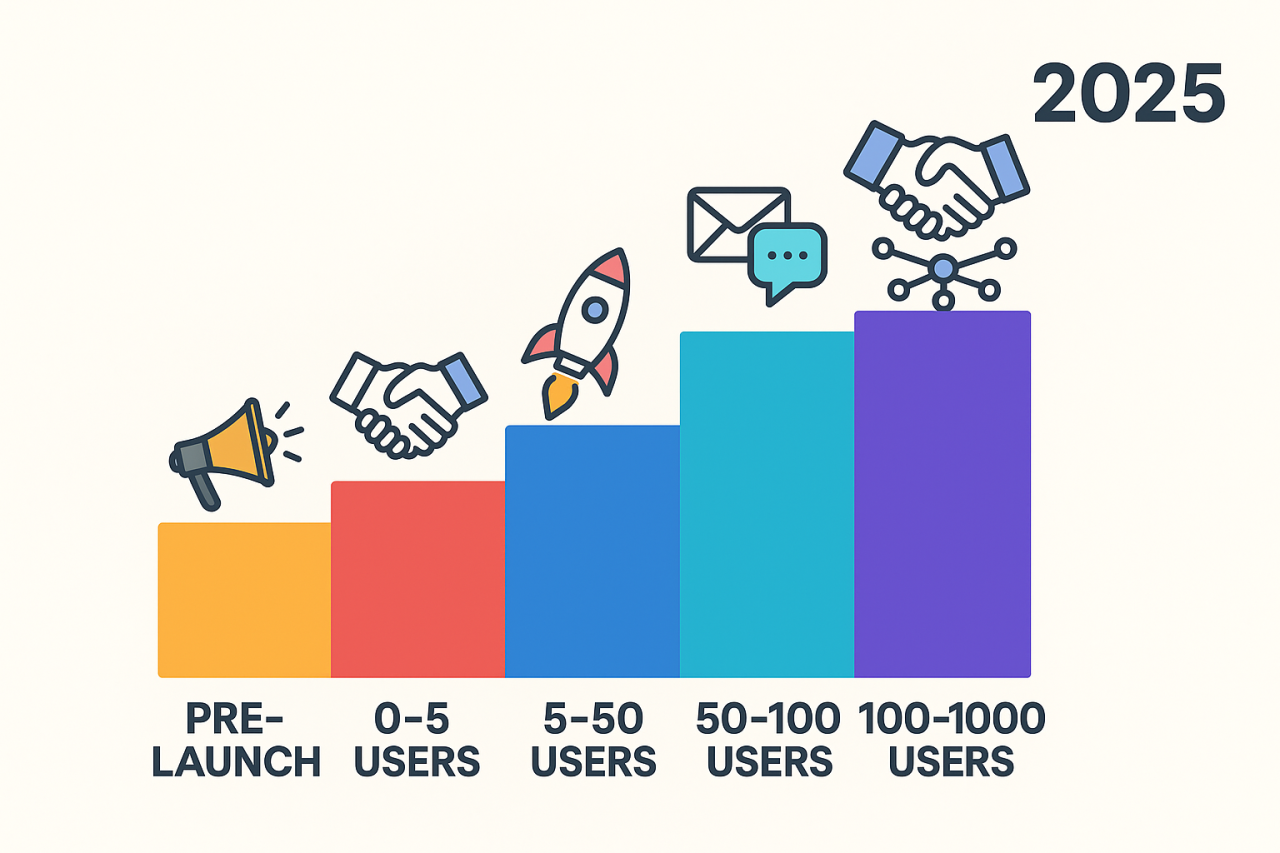

From 0 to 1,000 Customers: How to Reach 1,000 Customers for Your SaaS Platform

May 09 2025

Avoidable Tech Startup Mistakes: Six Pitfalls to Dodge

May 10 2025

The Broke Shopper’s Paradox—and What SaaS Makers Should Know

May 09 2025

Stop Building Blind: Why You Need to Know Your Niche Before Building a SaaS

May 22 2025