Copyright trolling is an unpleasant reality for many web developers and site owners. Imagine checking your inbox to find a scary legal-looking demand: someone claims you used an image or content without permission, and they want money. Are they a legitimate rights-holder or just trying to extort you? In this guide we’ll explain what these troll companies do, how to spot them, and what steps you (as a developer or website owner) can take to handle their letters calmly and confidently. We’ll also cover best practices for using free images (from sites like Pexels or Unsplash) and how to stay safe online. By the end, you’ll be better prepared to tell scams from real claims and know how to respond without panic.

May 13 2025 • 19 min read • 3667 words

How to Handle Copyright Trolls on Your Website

What Are Copyright Trolling Companies?

The internet is full of individuals and businesses trying to protect their images, videos, and text – and some go about it aggressively. Copyright trolling companies are organizations (often hired by photo agencies, media outlets, or individual photographers) that scour the web for any content that might have been used without a license. They then send out mass demand letters or emails to site owners saying things like “You used our copyrighted image; pay up or we’ll sue.” While legitimate copyright holders do enforce their rights, trolls have a few distinctive tricks:

- Automated scanning: They run bots or reverse-image searches across thousands of websites to spot potential violations. Anything from a missed credit on a blog photo to a background image on a forum can be flagged.

- Bulk demands: Instead of contacting one person at a time, trolls send out stacks of near-identical letters to dozens or hundreds of websites. It’s a numbers game – if even a few recipients pay, the troll makes money.

- High-pressure tactics: The letters often demand a steep “settlement” or “license” fee within a short time (sometimes just a week). They may cite large statutory damages (like tens of thousands of dollars per image) to scare you.

- Licensing after the fact: Many trolls frame their demand as an offer to “legitimize” your use by buying a retroactive license. For example, they might claim you can avoid a lawsuit by paying a one-time fee now. The catch is that this fee is usually many times higher than what a normal stock photo license would cost.

- Aggressive tone: Troll letters often read more like threats than polite notices. You may feel intimidated by formal language and legal jargon. Some even masquerade as legitimate law firms or “compliance” agencies.

Common names you might hear about include agencies like PicRights (often representing news organizations such as Reuters or AFP), Copytrack (a German-based photo-tracking service), or even well-known stock companies like Getty Images that have a reputation for tough tactics. However, the label “troll” usually applies when the emphasis is on extracting quick cash rather than genuinely defending creative rights.

Real-world example: A small blog once received a demand from Getty Images for an image they thought was free to use. In fact, the blogger had purchased the photo on a stock site (and even had an account showing the license), but Getty’s automated system didn’t pick up that detail and sent an “infringement” notice anyway. It took some digging and negotiation to show that the use was properly licensed, but the experience shows how easily a troll-like letter can arrive even when you did nothing wrong.

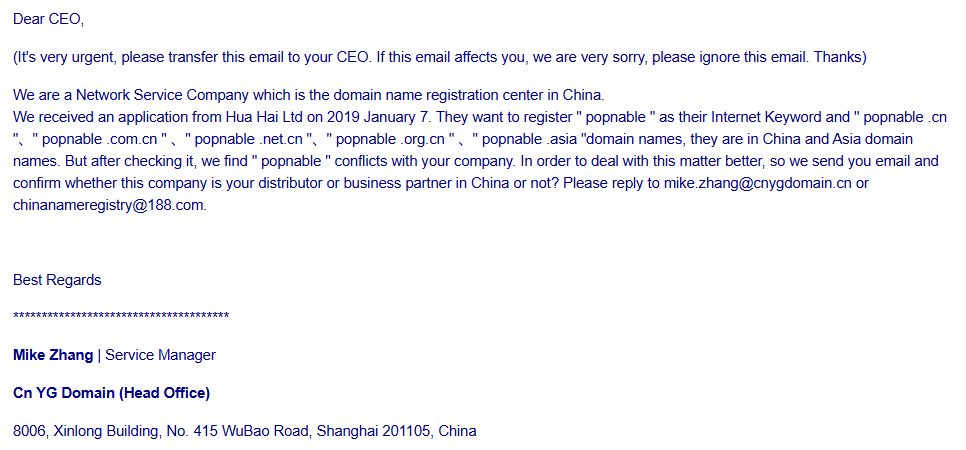

How to Tell If a Claim Is Legitimate or a Scam?

Getting a copyright demand letter can be shocking. The next step is to evaluate it carefully rather than immediately panicking. Here are practical tips to distinguish a valid claim from a troll scam.

Who sent the letter or email?

Google the name of the company or law firm. Known trolls like PicRights, Copytrack, or Voltage Pictures often pop up in forums and news stories about scams. If reviews and discussions label them as trolls, be cautious. However, note that even real companies can use third-party services; for example, PicRights has legitimately represented Reuters or Getty in the past. Look for a real street address, phone number, and lawyer’s name. If the contact info is sketchy (like a Gmail address or an overseas number), that’s a red flag. But also beware: some trolls pretend to be a big publisher or law firm. If you’re unsure, do some research or ask for referrals from others who’ve gotten similar letters.

A legitimate copyright claim will usually include specifics:

- Exact content identified: A genuine notice will point to the specific image or material you used (often a small low-res version or a URL). It may describe where it appeared on your site (like a blog post URL and date).

- Copyright owner and registration: Real owners often cite their registered copyright number (in the US) or at least name the work. If the letter just says “you infringed our copyright” with no evidence, be skeptical. When in doubt, ask the sender for proof of ownership (for example, ask them to provide the registration certificate or a screenshot of their work). An honest owner should be willing to show something; a scammer will dodge.

- Fee justification: Notice how they came up with the amount they’re demanding. An outrageous fee with no explanation (just “$4,400 for 200 images” or “$1,800 per image, pay by Friday”) is suspect. Legitimate copyright law does allow for statutory damages, but trolls often quote the maximum to frighten you. If a real company is charging, they’ll typically explain whether this is a license fee, a settlement for past use, etc. A mystery flat fee is more troll-like.

- Timeline and pressure: Troll letters often demand quick action (“Respond by 10/01 or face legal action.”) without giving you time to verify details. If the deadline is very short or they threaten immediate lawsuit, pause and look closer. Genuine cease-and-desist letters may still set a deadline, but they usually allow some room for discussion.

Do you recognize the image or content in question?

If no, it could be a mistake (e.g. the troll has the wrong URL or is targeting your site by a broad search). Politely reply that you don’t see that content on your site. Sometimes trolls harvest data poorly and may misidentify the infringing content. If yes, recall how you got it. If you took the image from Google Images or another website without permission, you might indeed owe something. But if you got it from a known source, check that source’s license or terms. For example, if it was on Pexels or Unsplash, it’s supposed to be free – you should mention that. If you purchased it from Shutterstock or Adobe Stock, you should have a receipt or account record. If you created it or have permission from the creator, note that. In any case, gather whatever proof you have (receipts, licenses, original files with metadata, email confirmations).

Look for typical “troll” behavior

Traditional legal protocol (and courtesy) often starts with a cease-and-desist letter asking you to take down the content, not immediately a settlement demand. If the first thing you hear is “pay now,” it’s likely a troll tactic. Trolls rarely clarify their relationship to the copyright. They might say “we represent the copyright owner” but won’t identify a real name or contact. A legitimate attorney or agent should clearly state who they represent (e.g. “on behalf of photographer John Smith”). If the demand is a round, high number (like $500 or $1,000) with no explanation, that’s fishy. Actual damages or license fees usually have some rationale (like a per-day or per-impression rate, or the fee you would have paid originally).

As mentioned, if they give you only a few days and insist on instant payment (especially to a random account or online form), be wary. You deserve time to review. Also, if they only accept Bitcoin or some strange payment, that’s definitely a scam sign. Sometimes trolls will keep bombarding you even after you remove the content. If their demands escalate without any real negotiation, they’re probably bluffing.

Check copyright registrations

If you want to be thorough and the amount is large, you can search the U.S. Copyright Office’s database (if the letter claims U.S. copyright) to see if the work is registered and who owns it. If the troll claims a registration number, you can call the Copyright Office to verify it. Many trolls don’t have registered copyrights (especially if they’re using some collective’s or uploading random images). Without registration, they actually can’t sue you in the U.S. until it’s registered. This doesn’t automatically negate their demand letter, but it’s useful info.

If the claim is for a substantial amount (hundreds or thousands of dollars) or you feel lost, consult a copyright attorney. Even an initial phone call can help you gauge how serious the claim is and what to say in response. Many lawyers will give a quick opinion for free or low cost. Sometimes just forwarding the letter to a lawyer can be enough to stop a troll in its tracks (they often back down if a real attorney is involved).

Remember, pause before you react. These demand letters are usually more threatening than legally forceful. You generally have time to verify. Don’t admit wrongdoing in your first reply, and don’t ignore them entirely (we’ll explain why next). For now, use the above checks to figure out if this might be a legitimate claim or likely a troll.

Using Images from Platforms Like Pexels

Many developers turn to free image libraries like Pexels, Unsplash, or Pixabay to avoid any copyright headache. These sites provide thousands of photos under very permissive licenses. For example, Pexels’ own license lets you “download, use, copy, modify or adapt the Content for commercial or non-commercial purposes” without paying or attributing (for images not marked CC0). Unsplash has a similar “free to use” license, with minor restrictions: you can’t sell the photo as-is (no prints on mugs or t-shirts that are just the unaltered photo) and you shouldn’t imply any person in the photo endorses your product without permission.

You can use Pexels/Unsplash images on your website, blog, app, etc., even commercially, without buying a license. You can crop them, filter them, or combine them with other elements. No need to credit the photographer (though giving credit is polite and encouraged when you can). These licenses explicitly allow editing. Unlike some Creative Commons rules, you don’t need to share your changes or keep it non-commercial. Go ahead and make it fit your design. You cannot simply re-sell the photo by itself. For example, you can use a free image as part of a design or marketing banner, but you can’t take it from Pexels/Unsplash and sell it as a print or NFT. Also, be mindful if an image includes a person or trademark; the license covers the photo’s copyright, but separate model or logo release issues can arise (though this is rare for typical web use).

Using these free images is generally safe from trolls. A copyright troll is unlikely to bother you if the image was legitimately obtained from Pexels/Unsplash under the terms. Those platforms intend their content to be used exactly for purposes like yours. However, here’s a caution: every now and then, content that someone didn’t own ends up on these sites. If someone uploads a copyrighted photo (e.g. a picture of the Eiffel Tower at night or a celebrity) without realizing they can’t actually do that, then you might think the image is free to use when it isn’t. In rare cases, trolls or even the original artist might then come after you.

Don't miss the real-world example below.

Premium content

Log in to continue

How to Respond to a Letter from a Trolling Company

If you determine the claim might be real, or even if you just want to play it safe, here’s a step-by-step plan for reacting to a demand letter without freaking out.

Stay calm and act promptly. Don’t panic, but don’t ignore the letter either. Ignoring a legitimate claim can make it worse (they might escalate to a lawsuit, even if it’s unlikely). At the same time, there’s no need to run to your wallet immediately. If you did use the image/content without permission, remove it from your site right away. This shows good faith and limits any “willful infringement” exposure. If the content is user-generated (like a forum post or blog comment), notify the user and consider issuing a DMCA takedown notice if you have one. Removing the content doesn’t admit liability; it simply prevents further unauthorized use.

When you do reply, keep it professional and polite. You can use bullet points or short paragraphs to cover each point clearly. For example:

- Acknowledge receipt: “Thank you for your notice dated [date].”

- State current action: “We have removed the image in question from our site while we review this matter.”

- Ask for clarification: If you’re unsure how the troll identified your site or if they can provide evidence, say so. For example, “Could you please provide the specific details (copyright registration number or title of the work) showing that you or your client owns this image?” This puts the ball back in their court. Often trolls don’t want to share anything, which can stall them.

- Assert your rights if you have them: If you legitimately believe you’re in the clear (say the image was from Pexels under license, or you credited it correctly), mention that politely and offer to forward any proof. “We sourced this image from [site] which licenses it freely. We’re looking into this but it appears we have the right to use it under that license.”

- Be factual, not emotional: Avoid apologies or admissions like “I’m so sorry, I didn’t mean to infringe.” Admissions can come back to haunt you. A firm, factual tone is better. For instance: “We were not aware of any infringement, but we take this matter seriously.”

- Point out any red flags (tactfully): If something in their letter contradicts what you know, gently note it. “Your letter states a trademarked image. However, our review suggests the image is public domain (or we had license number #12345 for it). Please clarify.”

If you do owe something (say you misused an image from a paid stock site), you have options. Negotiate down: Trolls often start high. It’s okay to counteroffer. You might say something like, “We understand the need to compensate the owner. The image is available on Shutterstock for $150 for a license; would you consider a similar fee instead of the $1000 demanded?” The Illinois Bar article on Getty advises checking stock prices and offering fair market value.

If you agree to pay a settlement (or license fee), insist on a written release or settlement agreement. It should say that once you pay the agreed amount, the issue is fully resolved and no further legal action will be taken. This protects you from the same troll coming back later with more claims. If they won’t budge and the amount is large, consult an attorney before paying. Sometimes just having a lawyer write back can make a troll drop its demand. Lawyers are good at parrying those “scare tactics.”

Even if you know it’s a troll, don’t be rude in your reply. Lawyers sometimes include your responses in court filings, and being respectful looks better. Don’t curse or berate the sender, even if you’re furious. Trolls count on angry reactions to show them you’ll pay to make them go away. Keep records of all communication (save emails, letters, notes of phone calls). Keep screenshots of your site with the image (and without it, after removal). If you talked to the stock site or the photographer, jot down what they said. This documentation can support your case if things escalate. After handling the immediate issue, make it a habit to use licensed content going forward. Some site owners decide to only use free CC0 images (public domain) or their own photos to avoid any doubt. Others pay for stock images upfront. You might also add clauses in contracts if you hire designers (stipulating images must be licensed) or keep a folder of receipts/license agreements for all paid assets on your site.

Real-world snippet: One small business removed the disputed image immediately and wrote back, “We have taken down the photo and kindly ask you to provide proof of ownership. We are willing to discuss a fair resolution.” The troll (PicRights) realized the site owner was on top of things and eventually dropped the demand. In another case, a blogger received a Getty letter and responded by showing he had bought the image from Shutterstock (complete with invoice). Getty backed off after seeing the evidence. These stories show that a measured response often works.

Difference Between Trolling Companies and Real Copyright Holders

It can be tricky to tell a legitimate rights holder apart from a troll, especially since real companies sometimes use strong language, too. Here are some pointers:

Who owns the content?

A real copyright holder is the original creator (or someone the creator granted rights to, like a publisher). A troll usually is not the creator. If the letter is from someone who merely licensed the image for enforcement, that could be either a legit agent or a troll-for-profit. Try to figure out who’s behind it. For example, if the letter says “Getty Images (or its subsidiary) owns this image,” Getty does own many photos. But Getty’s typical approach is to offer a license fee; they will rarely just send a random $1000 bill without explanation. By contrast, a troll letter might say “Getty Images representatives demand payment” but has no official Getty contact info, which is odd.

Formality and detail

Legitimate notices (from known companies or lawyers) often reference a specific work by title and date, and may offer a chance to license it. They might begin with a civil “cease-and-desist” tone. Troll letters, on the other hand, might bypass that formality and jump straight to “infringement, pay now or else.” Also, a true copyright owner will often send evidence like screenshots of how you used the image. Trolls sometimes include an image snippet, but it might not even be from your site – it could be a generic stock example.

Willingness to negotiate

Real copyright holders do want to be compensated, but they also have reputations to protect. If you ask for proof or explain your situation, a legitimate owner’s team is more likely to work it out reasonably. Trolls generally just want payment and will give you the cold shoulder if you question them. They aren’t interested in a fair market license; they want a quick win. A real claim will come with some backing (like “registered in the US Copyright Office, registration No. XX” or a date of creation). Trolls may ignore registration entirely, because many copyrights aren’t registered. Remember, without a registration (in the US), they can’t sue until it’s registered. Trolls don’t usually have registrations for all the images they tout, so they rely on fear instead of actual lawsuits.

Getty Images is a legitimate agency – but it’s earned a trollish reputation for how it chases unlicensed uses. Still, Getty does own its images, and it’s known for pursuing cases all the way to court occasionally. Meanwhile, companies like Righthaven (defunct) literally had no content of their own; they bought copyrights from defunct newspapers only to sue bloggers. That’s the classic troll move. Or consider a new start-up called CopybotX (hypothetical) that pops up claiming to enforce copyrights for any brand – if you’ve never heard of them, they might be a troll.

Copyright trolls can be scary, but you’re not helpless. The best defense is knowledge and preparedness. Finally, remember that prevention is the best medicine. Before putting any image on your site, ask: “Do I have the right to use this?” If the answer is yes (with proof to back it up), you’ve already dealt 90% of the problem. If you’re ever uncertain, replace the image with one you do have rights for. By following these practices and keeping your cool, you’ll protect your site and wallet from copyright trolls – and sleep easier knowing you can handle any surprise legal notice that comes your way.